What has SARS changed?

It may come as a surprise to many that tax and exchange control go hand in hand in terms of South African law. A person who is a “resident” for tax purposes is entitled to transfer up to R1 million abroad before they need pre-approval for any further amounts during a calendar year. A “non-resident”, however, needs pre-approval for every cent that is transferred abroad in a calendar year.

This generally means that, regardless of whether a person is a “resident” or a “non-resident”, they may, at some point, need to obtain a Tax Compliance Status (or “TCS”) Pin from SARS. This is issued when SARS approves the transfer of relevant funds abroad.

Beforehand, SARS made provision for an “Emigration” TCS Pin and for a “Foreign Investment Allowance” (“FIA”) TCS Pin. The former would apply to a person who is transferring funds out of South Africa following the cessation of their South African tax residency. The latter would apply in all other cases involving the transfer of funds out of South Africa.

These are now, effectively, one and the same, dubbed an “Approval for International Transfer” or “AIT”.

Slimmed Down, Beefed Up Process

The AIT Pin is now the go-to requirement when it comes to the approval of funds out of South Africa, i.e., more than R1 million for a tax resident, and every cent for a person who has ceased to be a tax resident, per year. This one document replaces the different approvals that were previously needed, simplifying things from this perspective, but the extent of information and documentation required by SARS is far, far more involved, and extensive.

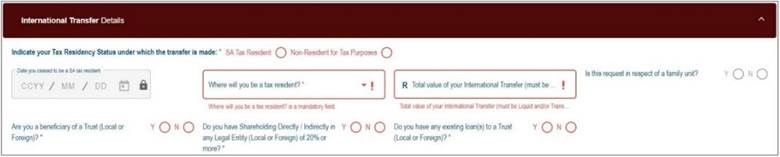

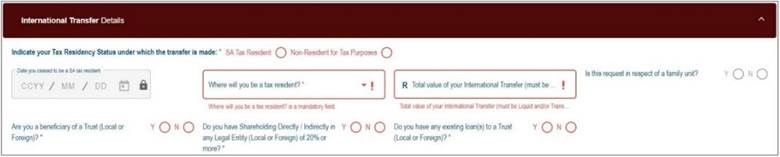

The first important disclosure to be made in the SARS form is whether the taxpayer is considered to be a “resident” or a “non-resident” for South African tax purposes. Where “non-resident” is selected, SARS will require that a Notice of Non-Resident Tax Status (i.e., a “non-resident confirmation letter”) be supplied.

Beyond this, before getting to the finer details that SARS requests, three more questions are asked of the taxpayer, i.e., regarding trust beneficiary status, shareholding in companies, and any loans to trusts.

If you happen to fall at this first hurdle, then hang on to your seat.

Count Your Chickens

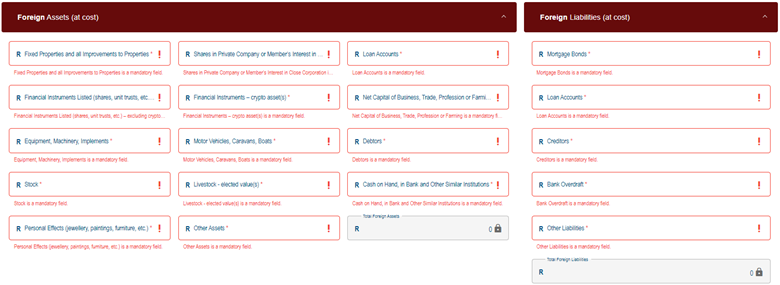

Previously, a taxpayer who applied for either an Emigration or FIA Pin from SARS was required to disclose their local assets and liabilities for the previous three years. Now, taxpayers are required to disclose both their local as well as their foreign assets and liabilities to SARS.

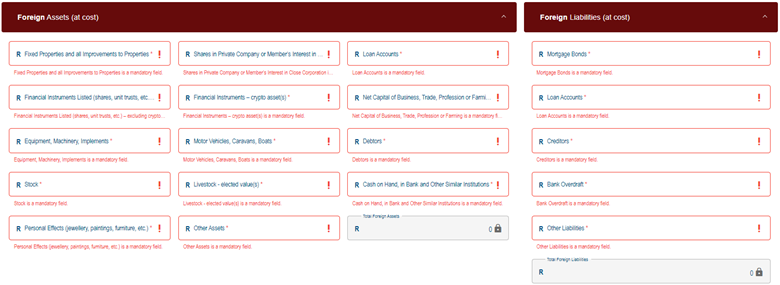

Merely in the Local Assets & Liabilities section of the form, SARS outlines no less than 19 mandatory fields in relation to different asset categories, spanning from fixed properties to crypto assets, and all the way to livestock. This is closely mirrored in the Foreign Assets & Liabilities section of the form.

It is also worth noting that every single asset listed in the Local and Foreign Assets & Liabilities forms must be allocated a value, and at cost. This is subject to further verification by SARS, in each case, and capturing the relevant information incorrectly may well lead to delay, if not further complications, either in respect of the application for the AIT Pin or further down the line with SARS.

Perhaps, then, please remember to count your chickens, lest you incorrectly disclose this item to SARS.

Another, new requirement is a request to the taxpayer for the sources where the value arose from. This, too, is subject to SARS verification and must be carefully selected. SARS provides nine different types of “source” for selection and a further option for “other” sources. With regard to each source of an amount to be transferred, further information will also be required thereon.

Enhanced Oversight and Enforcement

National Treasury has been promising to strengthen the tax treatment in respect of taxpayers with foreign interests, inclusive of a “more stringent verification process” and the triggering of a “risk management test” that includes the “certification of tax status and the source of funds”, since the 2020 Budget Speech.

Perhaps now spurred on by the recent, and unceremonious grey-listing of South Africa by the Financial Action Task Force in February this year, this silent-but-violent change to the TCS Pin request requirements has nevertheless come as a bolt out of the blue. Even South African authorised dealers (i.e., the banks), seem to have been caught unawares by this sudden change.

The introduction of robust, new disclosure requirements by SARS, however, is not itself completely out of left field. Last year, in an event held by the South African Institute of Taxation, in collaboration with Standard Bank and Tax Consulting SA, Natasha Singh from SARS’ High Wealth Individuals Unit, affirmed that SARS would seek to “enhance voluntary compliance”, and at the same time detect taxpayers “who do not comply” and “make non-compliance hard and costly” for them. These comments, read with SARS’ Strategic Plan for the 2021 – 2025 tax years, indicate that this forms part of its larger project to “[d]evelop and implement an enhanced methodology to detect and select non-compliance.”

This paradigm shift in the TCS requirements further affirms that SARS has a particular focus on the wealth of taxpayers, locally and abroad, and the basic standard of living for those seeking to financially emigrate or transfer their wealth offshore. Either way, this may now be a mainstay of the compliance burden that rests on taxpayers, and they must indeed be sure to tread lightly.

Perhaps it is evident, based on the extent of the information that is now requested by SARS, taxpayers are cautioned to measure twice and cut once, in terms of the disclosures made to SARS for the AIT Pin. It is recommended that these applications be proactively addressed by a qualified tax practitioner or attorney.

![2025-logo-[Recovered] Tax Consulting South Africa](https://www.taxconsulting.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2025-logo-Recovered.png)